Al Ching’s Love for Outrigger Canoeing Not Only Trickled Down to His Family but Also Across the South Bay

The saltwater family.

- CategoryPeople

- Written & photographed byKat Monk

- AboveDanny (front) and team (photographed by C. Silvester)

Growing up in Waikiki, Albert Kamila Choy Ching Jr. saw the ocean as his playground. Commonly known as Al, he is a legend in the outrigger world—the true embodiment of a natural-born waterman. Now 80, he has spent his entire life helping the South Bay community find that same love and passion for the ocean.

The Caputo family

After serving as a Marine during Vietnam, Al spent his weekends in college looking for places to play beach volleyball. Hermosa Beach became a favorite location, and he spent the next 25 years living on 9th Street across from Fat Face Fenner’s Falloon.

Al fondly remembers going with his roommates in 1964 to Little Hawaii, a small bar in Los Angeles, to “suck up some Coors.” By chance he met Sanford “Sandy” Kahanamoku, the cofounder of the Marina Del Rey Outrigger Canoe Club, who invited Al to watch him compete in an outrigger event in Santa Monica the next morning. Sandy’s uncle was Duke Kahanamoku—a legendary swimmer and paddler credited with popularizing the Hawaiian sport of surfing.

Outrigger, called an ama in the Pacific Islands, is rigged off the hull’s left side and connected by two parallel booms called iako. A fast-paced ocean sport with one or two lateral floats on the main hull, this particular type of racing differentiates itself from other paddling by pulling in the water rather than pushing. Paddlers reach out and grab the water, dragging their canoe forward, along with five teammates.

ABOVE: Al Ching and his son Danny

Al and five buddies went from spectators to competitors when a shorthanded coach recruited them to hop on a canoe and compete. “We raced in our undershorts and placed second,” Al remembers. “We went back to Little Hawaii that night and danced on top of the piano bar with a bunch of the paddlers. We were hooked.”

“As a grassroots sport, it is an opportunity for ordinary people to every once in a while do something extraordinary.”

After traveling to Marina Del Rey for years to paddle for Sandy, Al and his brother found an abandoned canoe buried in the sand next to a frat house in Hermosa Beach. A steal of a deal for $100, they completely refurbished it and named it Kaku—Hawaiian for barracuda. Motivated, they built a second boat from scratch using marine plywood. This boat, named Papio after Hawaiian game fish, had a vee-shaped bottom because the wood was too thick to bend.

In 1970, with two boats and a few other paddlers, they formed their own outrigger club, Lanakila, which means victory or determination in Hawaiian. Al soon became known as one of the best paddling technicians—an expert in training and technique. The club weathered many obstacles over the last few decades, but one thing that has stayed the same is their mission to accept anyone willing to learn how to paddle.

Ryland Hart

The club started launching their canoes from a small area of beach at the horseshoe portion of the Redondo Beach Pier underneath Tony’s. Al says not only was it a trek to get the canoes there, but “the surf some days could be huge and you could see yard sales [when someone loses control and everything goes flying] for 100 yards.”

Eventually Al looked for a place where they could properly launch and found a little spot in King Harbor. He stealthily set up shop on a small patch of dirt and just waited for someone to say something. Since it was hard to carry the paddles over the rocks and boulders, he found a bunch of scrap pieces of carpet and covered the ground to protect the paddlers’ feet. The launch area is now nicknamed “Carpet Beach.”

One day the city showed up. Al was nervous and certain the club was going to be kicked out of the harbor. They told him he needed to do it legally and offered him a rent price of $35 per month.

Needing to fill his canoes for business, Al distributed some recruiting flyers. A couple years later in 1978, he married one of those recruits, Erin Shea, a recent graduate of Redondo Union High School. Erin’s 7-year-old brother, Josh Crayton, was Al’s best man. Soon Al and Erin had two sons, Danny and Kawika. Josh was at their house almost every summer and soon was referred to as Al’s hanai child, Hawaiian for a child taken in by a family.

ABOVE: Aimee Spector, Julie Celestil, Dani Bell, Jill Schooler, Jeane Barrett and Mikayla Hart (photographed by C. Silvester)

The proverbial saying “The shoemaker’s son has no shoes” is not true for the Ching family. Both boys started paddling while they were still in diapers, and years later both became professional paddlers. Longtime club member Lori Vos remembers climbing into a canoe with Erin, looking down and seeing “Danny, as a toddler, lying down in the canoe between seats 5 and 6, drinking his bottle.”

After a big finish in Hawaii, the club started growing exponentially. One of the biggest draws was the luaus at the Chings’ home. The camaraderie of the members still lives on today.

Fifty years later, the club is one of the largest and most successful paddling organizations in the nation. Paddlers wake up when it is still pitch-black outside in order to prepare themselves for a day of paddling. A sea of red jerseys makes a powerful presentation on the blue water as up to 40 Lanakila teams get ready to compete. Ages can range from as young as 8 to 80 years old. At the end of a long day, many of the paddlers enjoy sharing stories over a few beers.

There are four seasons: Iron season, a six-person boat training up to 8 to 12 miles per workout; Sprint season, also a six-person boat with a 1.5- to 2-mile paddle; 9-man season, with six people in a boat at a time who rotate with three other paddlers from a nearby accompanying boat and typically paddle 18 to 26 miles; and One-man season, also known as OC1.

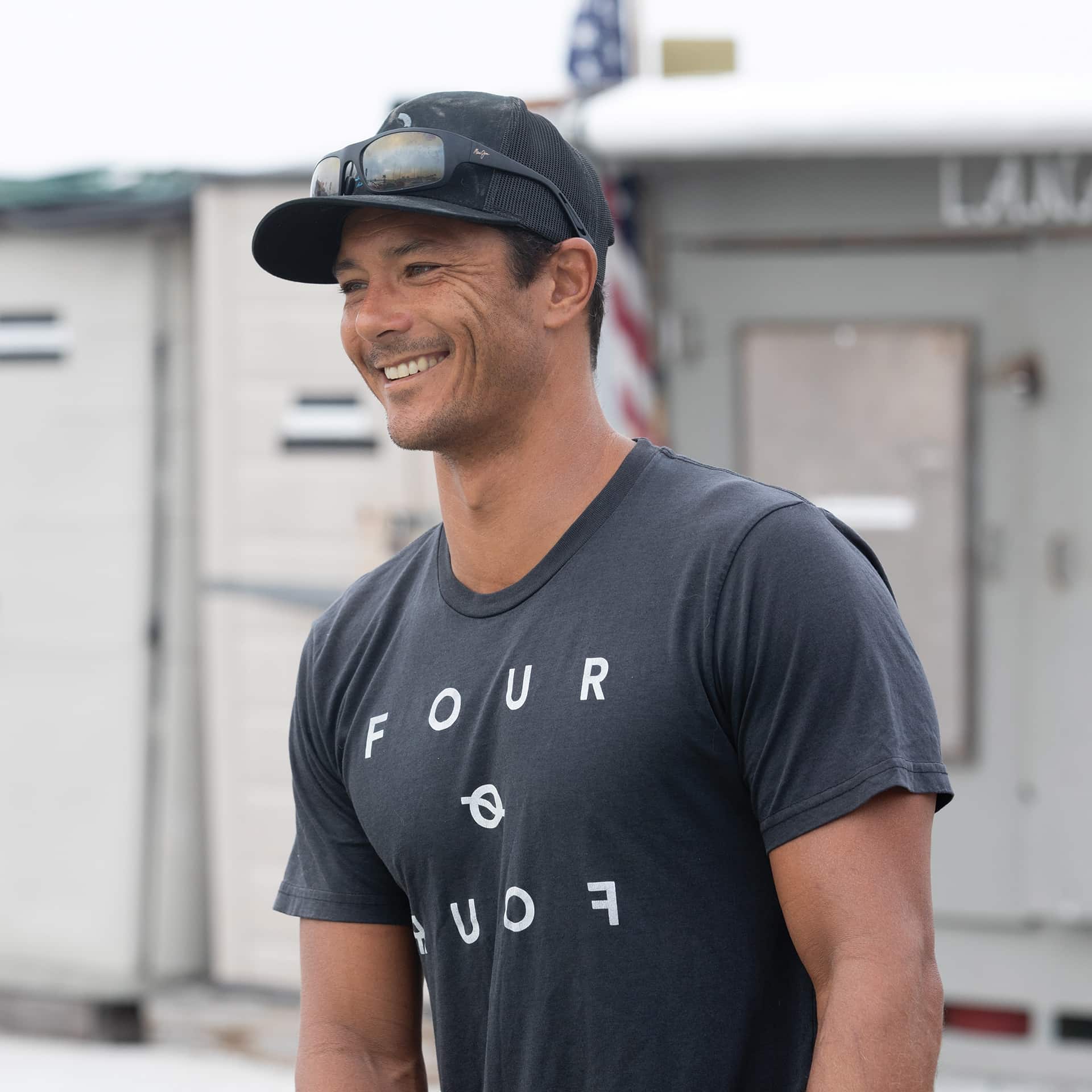

Danny Ching

Competitors typically participate in 12 to 14 races per year, culminating at the Catalina Crossing (a nine-person race) from Newport Beach to Catalina. This race—26 miles for women and 30 miles for men—is also referred to as the United States National Championship.

If you want to take it one step further, Hawaii hosts an international event—a 42-mile race called the Na Wahine O Ke Kaia. The women’s crossing is from Molokai to Oahu in late September. The men’s race, called Molokai Hoe, is hosted in October.

Al has turned over the business operations of the Lanakila Outrigger Club to Danny, who is also involved in three other businesses: 404 (specializing in race and touring boards), Hippostick (an all-natural stand-up paddle carbon company) and PaddleNinja (an online paddle training platform).

Danny is a multidisciplinary athlete who excels in elite activities that require a blade in the water. Rather than attract attention, he shies away from the limelight. Danny is the quintessential tall, dark and handsome waterman with a genuine smile. As talented as he is, he would be the last to let you know. The Hawaiian culture is steep in tradition, especially in respect for their kupuna or elders. Danny has the utmost respect for his father, and if Al asks him to do something he does it—even if it means being part of this story.

ABOVE: Jennifer McNally

One afternoon while Danny was coaching the men, a woman showed up to train due to a scheduling conflict. Although they didn’t exactly hit it off at first (she thought he was a bit arrogant), they soon fell in love. Now Leah and Danny are married with two daughters. As Lanakila is always a family affair, they can often be seen paddling with their young daughters, Kaimana and Kealia.

Lanakila churns out strong athletes, but whether you aspire to paddle for fun or go to a world-class level, there’s a place for everyone here. Members exercise, socialize and hang out together regularly. The club’s philosophy is to focus on who is there and not who isn’t there.

After a day of work, the mindset is to put the road rage away and be with other like-minded people. It is equally important for the club to teach respect for elders and reinforce the philosophy within their training. It is not uncommon to see multiple generations out there on competition dates.

“No one that has tried paddling has ever walked away saying, ‘I don’t ever want to do that again,’” states Josh. “As a grassroots sport, it is an opportunity for ordinary people to every once in a while do something extraordinary.”